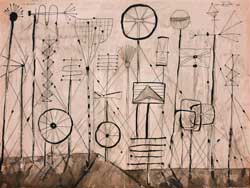

Otar Chkhartishvili belongs to the generation of the sixties - a generation which set it self the task of breathing new life into the pictorial language of art and to entrench free-thinking ways of life. Defiance of social realism was always at the heart of his creative career, while art served him as a means to throw down the Gauntlet to the authorities, as well as to society. For this reason life became an obstacle course for him, through which he had to navigate Otar Chkhartishvili is an influential figure of the Georgian underground. His artistic perceptions, pictorial techniques and experimental use of material have shaped him as an outstanding representative of avant-garde. He worked in a variety of visual art forms (painting, graphics, collage, sculpture) and genres (portrait, landscape, still life, abstract painting).

Excerpt from O. Chkhartishvili autobiography.

Historically the Chkhartishvilis come from Higher Jumati village in western Georgia. My father, Sandro Chkhartishvili, was born in 1893. His father died young, so it was his grandfather, Siko, who brought up four grandchildren. Grandpa Siko was said to be a well-read person. He spoke French and German and came from a well-off family. Prince Gurieli nominated Grandpa Siko for ennoblement, but this never happened. Instead, he was dispossessed as a kulak by the communists and died in 1921. His children subsequently fell under the scrutiny of the Cheka. After completing his schooling at the gymnasium, my father continued studying at the law faculty of Saint-Petersburg University, from which he graduated in 1916. By 1921 my father owned several trade centers in the Guria region and supplied them with difficult-to- obtain goods from abroad. As he used to say, he had traveled to all large countries except for England. From 1921 father often had to change his whereabouts in order to elude the Cheka. This way he avoided Stalin's repressions of 1937. Until 1929 my father had a wife who gave birth to four children but it was his second wife, my mother, 17-year old Natalia, who happened to bring them up. My mother, Sviridova by name, was a descendant of the Kuban Cossacks. She arrived in Georgia in search of work in 1932, during the Golodomor in Ukraine. Natalia and my father produced three more children.

I was born on July 5,1938, in the town of Kobuleti. Shortly after that our family moved to the village of Varche in Gulripsh region. In 1945 I went to the local four-year primary school. Our house stood quite close to the Black Sea and I often went to the seashore. I used to sit alone entranced, gazing at the sea. My dreams floated over the horizon. Sometimes, tiny, snow-white, toy-like ships were seen far away, some of them leaving a dark trace along the entire line of the horizon, which after a long while finally merged with the blue of the skyline, slightly changing its tint.

I dreamt of becoming a sailor. I never told anyone this until now, as I felt like someone would steal my dream and it would not be mine any more. At that age I had never seen a real picture and had not the slightest idea of who or what a painter was; neither had ever seen a color reproduction, drawing paper or color paints, so like a primitive man, I used to draw scenes of war on walls with a firebrand.

In 1951 we moved to Makharadze (present day Ozurgeti – city in Western part of Georgia). My father built a house near the Natanebi River. All my teenage years were spent by the river.. I cannot say I have good memories of my school time, for none of my teachers managed to make me like their subject, so I kept drawing during their lessons.

In 1960 I entered Tbilisi State Academy of Arts. As a rule, people love to recollect their student years as a time of joyful feasts and all sorts of adventures, but for me this was a period of studying and hard work. I read vastly, trying to fill in the educational gap of my school time. I worked hard to cultivate myself, as I well realized there was no other way to genuine art. To be frank, I dreamt of becoming a famous artist. I used to go to Moscow and Leningrad on holidays to visit museums and bring back suitcases full of books on art. On April 12, 1961, together with my fellow students, I organized for the first time an unauthorized exhibition and sale dedicated to the Day of Painters, in front of the Opera House. However, this was viewed as political activity by the authorities, who threatened us with arrest. We were protected and supported by the outstanding Georgian artists Lado Gudiashvili and Elene Akhvlediani. We all were questioned and strictly warned not to repeat any similar action next year...

Soviet art had its concept - Socialist Realism, which meant to reflect the everyday life of a Soviet individual in a realistic way. However, the conformist art workers of the empire veiled the reality by churning out powered-up, glossy portraits of Lenin and Stalin to be hung in offices. Any trend of art except for Social Realism was ruthlessly prosecuted. Non-ordinary thinking was also prohibited. Upon successfully graduating from Tbilisi State Academy of Arts in 1966, I was delegated to Makharadze to work (without salary) as a stage-lighting designer at the local drama theatre. From 1968 my creative activity was full of confrontation, for I could not conform to the false socialist philosophy concocted by the communists. That was why, from that time onwards up to 1990 I was labeled as an anti-Soviet figure. In 1973, by the decision of the secretariat of the Union of Artists of Georgia, each artist had to present a painting once a year at a jury-free single-painting exhibition; this would help the KGB to identify dissidents among artists. This kind of exhibition was first opened at the House of Art Workers, where my collage "Ring" was exhibited and found radical by the Union of Artists and irritating for the adherents of Socialist Realism. This is how I was entrapped by the KGB.

Even before I entered the Academy of Arts I happened to be introduced to Elena Semionovna, a correspondent of the journal "Decorative Art", who wanted to write an article on my participation in the exhibition of self-taught painters. Later, with the help of this lady, I came to know the number-one Soviet dissident, Daniel Siniavski, in Moscow as well as the Muscovite nonconformist artists, the famous writer Boris Pasternak, the poet Sergei Mikhalkov, Chuvash poet Gennadi Aigi and plenty of other forward-thinking persons. In 1974 in Moscow, at 5 o'clock one morning, an outdoor exposition of works of nonconformist artists was held, hosted by Muscovite poet and collector Alexander Glezer. He notified all the embassies in Moscow in advance and sent them invitations. Early that very morning the event was recorded and transmitted to the world's leading media. By 11 o'clock in the morning the exhibition was suddenly surrounded by bulldozers from every side crushing everything in their way with no mercy for people or newly-planted trees. The exhaust fumes spread by the bulldozers were so thick that nobody was visible. It was hard to guess who was looking for whom. Those who managed to take their works away saved them. This assault resembled the "Battle of Borodin". In 1975 I took part in an exhibition of nonconformist painters arranged in Glezer's emptied three-room apartment in Moscow. The exhibition presented works of the same "Bulldozer Exhibition" artists. Among the exhibits there was a sculptural composition by Ernst Neizvestni. The participants of the exposition were hassled by the KGB men, so we had to call for a group from the US embassy to protect us from Soviet agents.

In 1976 I submitted my work "Rhythm" (collage) to the National Picture Gallery in Tbilisi for its traditional spring exposition. In 1977 I exhibited another collage of mine, "Elephant" (now kept in the USA, at the Zimmerli Art Museum) at the same gallery. Throughout this entire period I pushed my works for exhibition by force, but there was no reaction to the novelty and no articles were published.

In 1984, I organized an avant-garde group of seven artists, whose exhibition was only held in 1988, at the Artist's House of Tbilisi, after a four-year struggle with authorities. It was the first joint exposition of Georgian avant-garde painters, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the birth of the great Georgian artist, David Kakabadze. The exhibition brought about a wind of change to Georgian art of the 1970s, having become an event. This very exhibition moved to Kharkov in the autumn of 1988, then to the exhibition hall of "Mziuri", the Georgian cultural and trade center in Moscow.

For thirty years I stubbornly adhered to my principles without betraying them for a single second. I never expected any profit during my working process; neither did I imagine that fortune would ever smile on me. My creative work was a strive against totalitarianism and atheism in the first place, which I was eagerly involved in, as it was my life work and nobody could do my part of it.

Simon Japaridze, who led all important ascents of Kavkasioni in 1926-28, initiated researchers into the study of the

Simon Japaridze, who led all important ascents of Kavkasioni in 1926-28, initiated researchers into the study of the